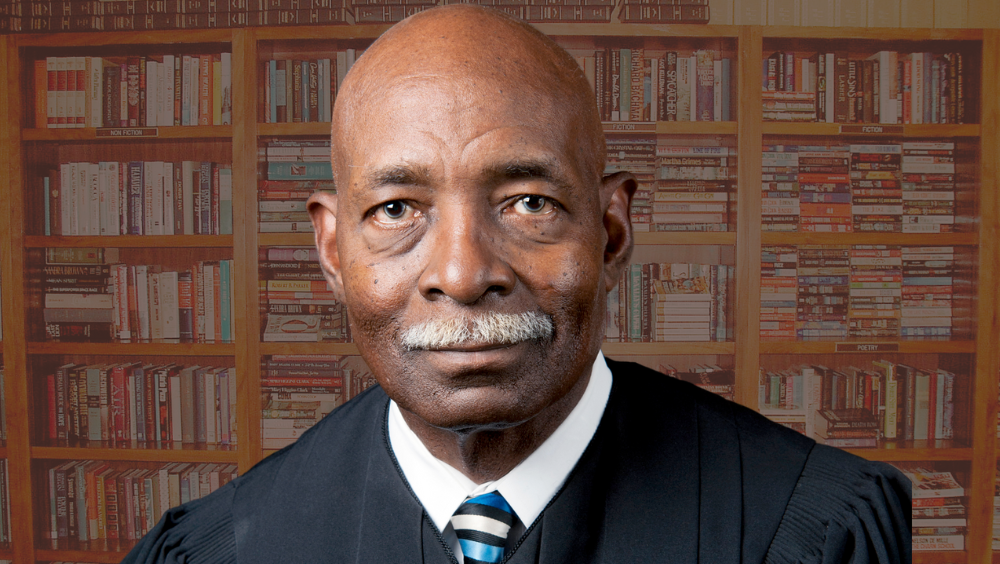

Robert D. Rucker, a native of Gary, Indiana, was appointed to the Indiana Court of Appeals in 1991 and was the first African in America to serve in that Court, and was thereby the first African in America to serve as an appellate judge in Indiana. In 1999 he was the 105th person, and the 2nd African in America, appointed to the Supreme Court of Indiana, from which he retired in 2017.

Mark Steven DOUGLAS (Shaka SHAKUR), Appellant-Defendant, v. STATE of Indiana, Appellee-Plaintiff

No. 45A05-9212-PC-439.

Court of Appeals of Indiana, Fifth District.

Sept. 12, 1994.

Judge Rucker, dissenting:

I dissent. I disagree with the majority’s conclusion that the jury was properly instructed on the element of specific intent. I also disagree with the majority’s conclusion that Douglas was not entitled to an instruction on the defense of intoxication.

… The specific jury instruction at issue in Smith was as follows: “You are instructed that the essential elements of the crime of attempted Murder which the State of Indiana must prove beyond a reasonable doubt are the following: 1. That the [Defendant] knowingly, 2. Engaged in conduct that constituted a substantial step toward the commission of Murder.”

Nowhere in the instruction was there a statement to the effect that if the defendant were to be found guilty of attempted murder, then there must first be a finding that when he engaged in the proscribed conduct, he intended to kill the victim. The court observed:

“Thus, we are left with instructions which would lead the jury to believe that the Defendant could be convicted of attempted murder if he knowingly engaged in conduct which constituted a substantial step toward the commission of murder… An instruction which correctly sets forth the elements of attempted murder requires an explanation that the act must have been done with the specific intent to kill.”

The offending instruction, in that case, is essentially the same as the one before us.

Underscoring the significance of informing the jury on the intent element in crimes of attempt, our Supreme Court has held:

“By definition, there can be no ‘attempt’ to perform an act unless there is a simultaneous ‘intent’ to accomplish such act. Simply stated, in order to commit a crime, one must intend to commit that crime while taking a substantial step toward the commission of the crime.” Spadlin vs. State (1991).

The rationale justifying reversal in the forgoing cases is no less compelling here. The instructions are essentially the same, and the result reached should be the same as well. The law is clear that it is a fundamental error to fail to instruct the jury on an essential element of the crime of attempted murder, namely, an intent to kill the victim. Woodcox v. State (1992). However, whether the case involves attempted robbery or attempted murder, there nonetheless “can be no ‘attempt’ to perform an act unless there is a simultaneous ‘intent’ to accomplish such act.” Spradlin. In this case, the instructions do not Impose upon the State the burden of proving an essential element of the crime, viz., an intent to take property from another person or from the presence of another person. Accordingly, I would reverse Douglas’s conviction and remand this cause for a new trial.

The majority’s treatment of the trial court’s instruction on the intoxication defense is even more troubling. Citing Weyls vs. State (1992), the majority takes the position that there was an inadequate evidentiary basis in this case to justify giving an Instruction on the intoxication defense. However, reliance on Weyls is misplaced. In that case, the defendant complained that the trial court erroneously refused to give a tendered Instruction on the defense of intoxication. Relying on well-established case authority, this court observed that when reviewing a trial court refusal to give a tendered Instruction, we consider 1) whether the instruction correctly states the

Law, 2) whether the evidence of record supports giving the instruction, and 3) whether the substance of the tendered instruction was covered by other instructions. We then held the evidence of record did not support giving Weyls’s tendered instruction, and thus, the trial court did not err in refusing to give it.

Unlike Weyls, this case does not involve the trial court’s refusal to give an instruction. Rather, it involves the trial court giving an instruction based on a statute that has since been ruled void and without effect. Further, in giving the erroneous instruction, the trial court itself acknowledged “there was some evidence introduced during the trial indicating that the defendants may have been intoxicated at the time of the offense…” Obviously, there was evidence of record to support giving of an intoxication defense instruction. Otherwise, the trial court would not have found it necessary to dispel the Impact of such evidence. The majority’s position that there was an inadequate evidentiary basis, in this case, to justify giving an instruction on the defense of Intoxication not only second guesses the trial court on this point but, more importantly, invades the province of the jury.

… the erroneous Instruction given by the trial court removed Douglas’s intoxication defense from the Jury’s consideration. In my view, the error here was fundamental. It constituted a clear, blatant violation of basic and elementary principles, and the resulting harm was substantial. When an error in the giving of a particular instruction “misleads the jury as to the law of the case,” then reversal is justified. Walker vs. State (1986). Thus, in addition to the reasons set forth in Section 1 above, I would also reverse Douglas’s conviction on these additional grounds and remand this cause for a new trial.

Featured photo: Robert D. Rucker